Burnout has become one of the most discussed topics in the corporate world. The explanation, however, often follows a predictable path: insufficient resilience, poor stress tolerance, or gaps in emotional skills. Organizational responses tend to mirror this narrative, prioritizing behavioral training, wellness initiatives, mindfulness sessions, and campaigns promoting work–life balance.

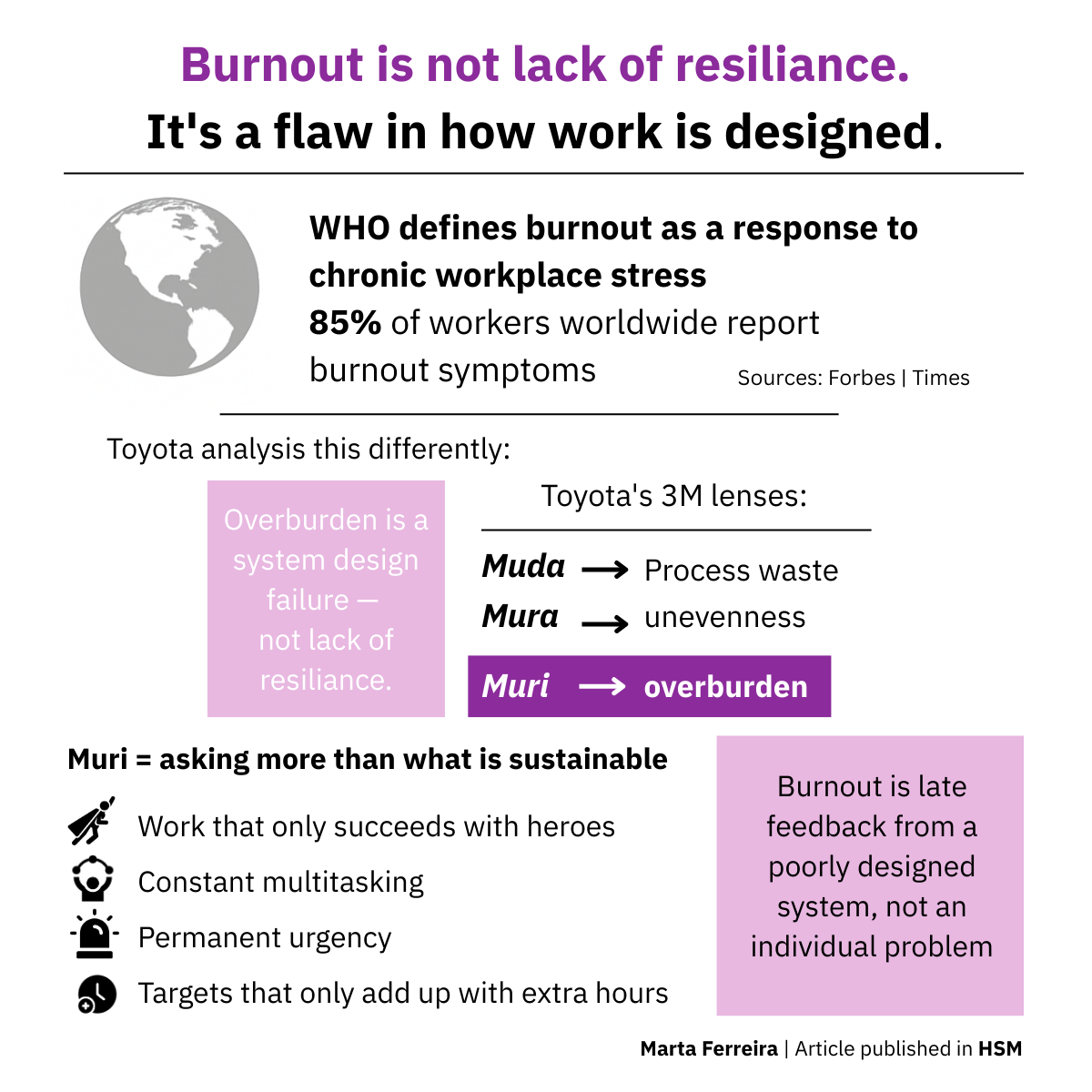

Although these initiatives may offer limited benefits, evidence suggests they fail to address the root of the issue. The World Health Organization defines burnout as a response to chronic workplace stress that isn’t managed successfully — not as a lack of individual resilience1.

Recent global surveys reflect this reality:

- A major study found that 85 % of workers worldwide report burnout symptoms due to workplace conditions — not because they lack grit2.

- Another report suggests that more than 75 % of people experience some form of burnout at some point in their careers3.

These numbers aren’t anecdotes. They’re systemic patterns.

If burnout were about character, only a handful of people would suffer it. Instead, most people do, across industries, age groups, and cultures.

When a phenomenon reaches this scale, individual explanations lose credibility. In any other management context, patterns this consistent would be interpreted as a systemic failure — not as a widespread deficit in personal resilience.

Burnout as Feedback From the System

Systems deliver exactly the outcomes they are designed to produce. When work consistently demands effort beyond sustainable limits, the impact rarely appears as a one-off incident. Instead, it accumulates over time as chronic exhaustion.

This perspective is not new. Long before burnout became a mainstream corporate concern, the Toyota Production System (TPS) already treated overload as a clear signal of poor work design. Contrary to the oversimplified notion of lean thinking as “doing more with less,” TPS has always emphasized stability and sustainability. Its underlying philosophy assumes that work must be designed around human capabilities, minimizing unnecessary physical, mental, and cognitive strain.

Within this framework, one concept is particularly relevant: Muri.

What Muri Is — and Why It Matters

Muri refers to unreasonable or excessive overload placed on people. It is not limited to physical effort. In administrative, service, or knowledge-based work, Muri most often manifests as cognitive overload: constant decision-making, frequent shifts in priorities, unclear standards, and an ongoing need to adapt on the fly.

In practice, Muri becomes visible when:

- The system only functions through extraordinary effort from certain individuals

- Targets are defined without regard for real team capacity

- Priorities shift constantly, with little or no clear rationale

- Improvisation replaces well-designed processes

- Overtime and multitasking become standard practice

These are not signs of high performance. They are indicators that people are compensating for structural weaknesses. When Muri becomes normalized, organizations begin to rely on “key individuals” to absorb instability. Over time, the cost emerges in the form of exhaustion, declining quality, rework — and eventually, burnout.

Seen through this lens, burnout stops being an isolated psychological issue and becomes delayed feedback from a poorly designed system.

What This Means for Leaders and Organizations

At Toyota, overload was never framed as an individual attitude problem. The principle of respect for people has always gone hand in hand with the responsibility to design work systems that are predictable, stable, and sustainable.

For leaders and management professionals, this requires a shift in focus. Before investing exclusively in initiatives aimed at increasing resilience or engagement, it is worth questioning the very design of work itself.

A few diagnostic questions can help surface the issue:

- Where does work only get done through constant extra effort?

- Who holds the system together when things go off plan?

- Is the pace of work predictable — or mostly reactive?

- Do processes reduce cognitive load, or add to it?

These questions move the conversation away from individual behavior and toward organizational accountability.

This perspective on Burnout is essential for anyone leading a journey of Organization Transformation.

Perhaps meaningful progress in addressing burnout will not come from asking people to become more resilient — but from designing systems that do not depend on human exhaustion to function.

1 https://www.forbes.com/sites/jasonwalker/2025/10/23/the-resilience-paradox-how-its-fueling-workplace-burnout/

2 https://www.thetimes.com/business/companies-markets/article/85-percent-workforce-burnout-mental-health-reed-pvcqwt3l3

3 https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2026/feb/15/75-of-people-suffer-from-burnout-what-you-need-to-know

Disclaimer:

Originally published in Portuguese by HSM Management (Brazil)

Infograms: